Acoustic metric

In mathematical physics, a metric describes the arrangement of relative distances within a surface or volume, usually measured by signals passing through the region – essentially describing the intrinsic geometry of the region. An acoustic metric will describe the signal-carrying properties characteristic of a given particulate medium in acoustics, or in fluid dynamics. Other descriptive names such as sonic metric are also sometimes used, interchangeably.

Contents |

A simple fluid example

For simplicity, we will assume that the underlying background geometry is Euclidean, and that this space is filled with an isotropic inviscid fluid at zero temperature (e.g. a superfluid). This fluid is described by a density field ρ and a velocity field  . The speed of sound at any given point depends upon the compressibility which in turn depends upon the density at that point. This can be specified by the "speed of sound field" c. Now, the combination of both isotropy and Galilean covariance tells us that the permissible velocities of the sound waves at a given point x,

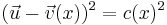

. The speed of sound at any given point depends upon the compressibility which in turn depends upon the density at that point. This can be specified by the "speed of sound field" c. Now, the combination of both isotropy and Galilean covariance tells us that the permissible velocities of the sound waves at a given point x,  has to satisfy

has to satisfy

This restriction can also arise if we imagine that sound is like "light" moving though a spacetime described by an effective metric tensor called the acoustic metric.

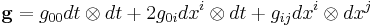

The acoustic metric

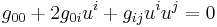

"Light" moving with a velocity of  (NOT the 4-velocity) has to satisfy

(NOT the 4-velocity) has to satisfy

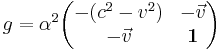

If

where α is some conformal factor which is yet to be determined (see Weyl rescaling), we get the desired velocity restriction. α may be some function of the density, for example.

Acoustic horizons

An acoustic metric can give rise to "acoustic horizons" (also known as "sonic horizons"), analogous to the event horizons in the spacetime metric of general relativity. However, unlike the spacetime metric, in which the invariant speed is the absolute upper limit on the propagation of all causal effects, the invariant speed in an acoustic metric is not the upper limit on propagation speeds. For example, the speed of sound is less than the speed of light. As a result, the horizons in acoustic metrics are not perfectly analogous to those associated with the spacetime metric. It is possible for certain physical effects to propagate back across an acoustic horizon. Such propagation is sometimes considered to be analogous to Hawking radiation, although the latter arises from quantum field effects in curved spacetime.

Acoustic metrics and quantum gravity

Since acoustic metrics share some statistical behaviours with the way that we expect a future theory of quantum gravity to behave (such as Hawking radiation), these metrics have sometimes been studied in the hope that they might shed light on the statistical mechanics of actual black holes. Some people have suggested that analog models are more than just an analogy and that the actual gravity that we observe is actually an analog theory. But in order for this to hold, since a generic analog model depends upon BOTH the acoustic metric AND the underlying background geometry, the low energy large wavelength limit of the theory has to decouple from the background geometry.

See also

- Analog models of gravity

- Hawking radiation

- gravastar

- acoustics

- metric (mathematics)

- quantum mechanics

- quantum gravity

References

- W.G. Unruh, "Experimental black hole evaporation" Phys. Rev. Lett. 46 (1981), 1351–1353.

- – considers information leakage through a transsonic horizon as an "analogue" of Hawking radiation in black hole problems

- Matt Visser "Acoustic black holes: Horizons, ergospheres, and Hawking radiation" Class. Quant. Grav. 15 (1998), 1767–1791. gr-qc/9712010

- – indirect radiation effects in the physics of acoustic horizon explored as a case of Hawking radiation

- Carlos Barceló, Stefano Liberati, and Matt Visser, "Analogue Gravity" gr-qc/0505065

- – huge review article of "toy models" of gravitation, 2005, currently on v2, 152 pages, 435 references, alphabetical by author.